“A commodity seems at first glance to be a self-evident, trivial thing,” Karl Marx famously wrote in Das Kapital. “The analysis of it yields the insight that it is a very vexatious thing, full of metaphysical subtlety and theological perversities.” “Detail of a Detail,” Luxembourg & Dayan’s second exhibition devoted to the late Italian realist painter Domenico Gnoli, was riddled with superficially innocent, deeply vexing items: the prim knot of a red necktie, a tooled-leather brogue, a starchy white collared shirt, a floral damask duvet. Violently uprooted from their respective milieus and impacted against the picture’s surface, these artifacts of postwar Italy’s embourgeoisement are fully frontal and too close for comfort, ostensibly withdrawn from meaning yet disposed to fetishistic vitalization.

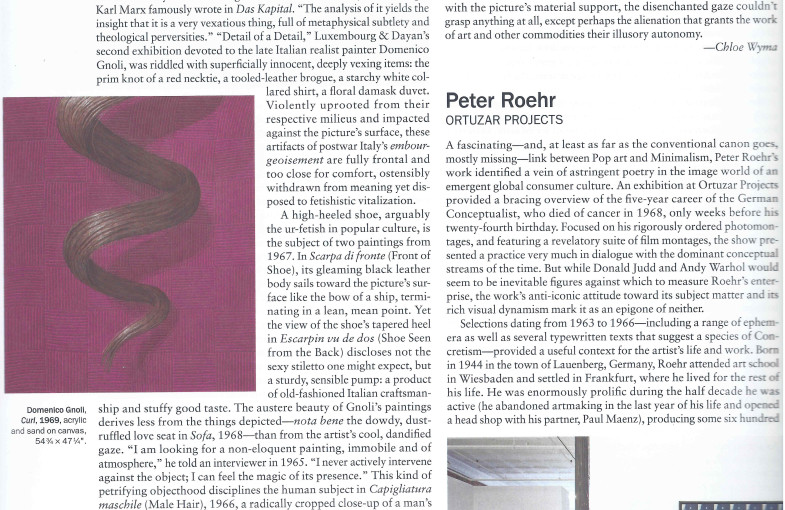

A high-heeled shoe, arguably the ur-fetish in popular culture, is the subject of two paintings from 1967. In Scarpa di fronte (Front of Shoe), its gleaming black leather body sails toward the picture’s surface like the bow of a ship, terminating in a lean, mean point. Yet the view of the shoe’s tapered heel in Escarpin vu de dos (Shoe Seen from the Back) discloses not the sexy stiletto one might expect, but a sturdy, sensible pump: a product of old-fashioned Italian craftsmanship and stuffy good taste. The austere beauty of Gnoli’s paintings derives less from the things depicted—nota bene the dowdy, dust-ruffled love seat in Sofa, 1968—than from the artist’s cool, dandified gaze. “I am looking for a non-eloquent painting, immobile and of atmosphere,” he told an interviewer in 1965. “I never actively intervene against the object; I can feel the magic of its presence.” This kind of petrifying objecthood disciplines the human subject in Capigliatura maschile (Male Hair), 1966, a radically cropped close-up of a man’s hairline. His meticulously groomed strands spring from an immaculate side part, each one striating the painting’s glistening oil-black surface like a record groove. In Curl, 1969—the final work in a series from Gnoli’s acclaimed New York debut at Sidney Janis Gallery in 1969 (only three months before his death from cancer at age thirty-six)—a lock of hair congeals into a sculptural helix isolated against a tessellated maroon ground. Here, notwithstanding the artist’s claim that he never “wanted to distort,” style and hygiene become so extreme that they thrust his objects into abstraction.

Gnoli’s canvases are encrusted with sand and marble debris mixed into acrylic paint, which leave behind cystic deposits that irritate and corrupt the works’ slick illusionism. Suggestive of fresco, these grainy surfaces nod, with a creeping melancholia, to a historical moment predating the commodity culture the paintings so dapperly depict. Gnoli traced the “non-eloquent” tradition back to Italy in the fifteenth century, when the integration of painting and architecture seemed to secure art’s social rootedness and ritual function. The structuring antinomies—between fetish and fresco, seductive illusion and repellent facade, desirable image and dumb matter—that give Gnoli’s work its special anxiety were here clarified by the juxtaposition of two paintings with self-explanatory titles. In Red Tie Knot, 1969, the eponymous scarlet neck-tie’s voluptuous form floods the canvas, a commodity engorging the eye with the marvelous perversity that so bedeviled Marx. Brick Wall, 1968, Gnoli’s version of a “wall painting,” is very unlike Giotto’s or Piero della Francesca’s. Gridlocked by obdurate masonry coextensive with the picture’s material support, the disenchanted gaze couldn’t grasp anything at all, except perhaps the alienation that grants the work of art and other commodities their illusory autonomy.