The artist has created an explanatory video:

Since the 1970s, Mark Flood has occupied the role of an “artist’s artist,” a protected insider’s secret for those who have encountered his work or known his band Culturcide. Working in relative obscurity in his native Houston, Texas, Flood came of age in a Big Oil town in boom times and witnessed at close range the onslaught of corporate and celebrity culture that came to define America in the 1980s. Situated at the intersection of art, music and social critique, his art rescues the relics of abandoned popular culture from the realm of waste in collages that transform celebrities into grotesque caricatures; altered advertisements stripped of their commercial identities; and found ephemera transposed across canvases. Every corner of American mass cultural output provided fodder for Flood’s early works; no popular culture figure or brand— whether David Lee Roth or Newport cigarettes—was safe from his scissors or microphone. Funny and irreverent, but also pointed, poisoned, and poignant, Mark Flood’s early work is both an enduringly powerful lens on America and a sophisticated, anarchic continuation of high art’s love affair with the readymade.

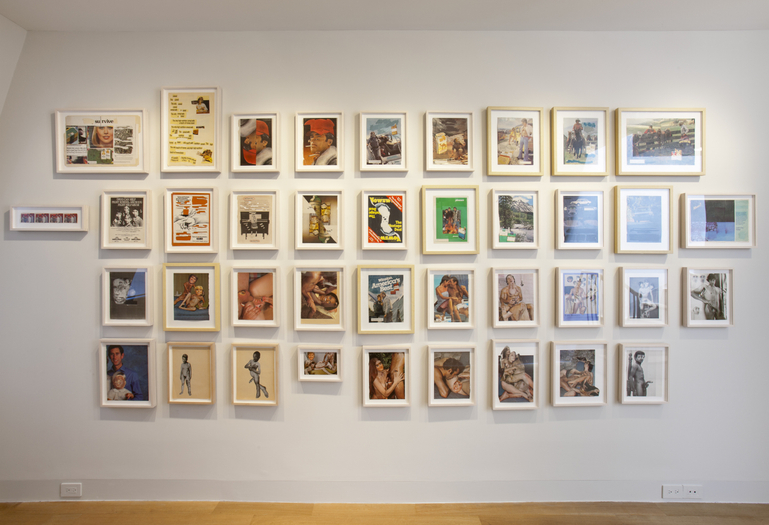

Beginning July 18, 2012, Luxembourg & Dayan will present The Hateful Years, the first survey ever devoted to Mark Flood’s seminal work of the 1980s. Curated by Alison Gingeras, the exhibition brings together more than one hundred of the artist’s paintings and collages, which will fill the gallery’s entire townhouse at 64 East 77th Street.

The Hateful Years will remain on view at the gallery through September 29, 2012. The show will be bracketed by an introductory contextual installation of Flood’s specially made new Lace Paintings on the gallery’s ground floor, and an ‘80s mise-en-scène on its top floor. It is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue featuring essays by Alison Gingeras; John Dogg; curator and critic Bob Nickas; art critic Ellen Langan, director of Maccarone; and Alissa Bennett, art critic and associate director of Luxembourg & Dayan.

Less a series of appropriative gestures than an act of resuscitation, Flood’s riot of ‘80s art in The Hateful Years examines the vapor trails of culturally exsanguinated people, places and objects in order to take the measure of culture. Though his technique ranges from craft-intensive collage and painting, to found objects assaulted by heavy-handed alterations, the artist’s work consistently functions without benefit of ironic distance. He knows and loves his subjects, and whether we are presented with images of pop singers whose faces have been decimated or found landscapes transformed into crudely rendered advertisements for fast food and gasoline, Flood’s concerns are specific to American desires and their resulting waste.

Whether through Culturecide’s signature deadpan lyrics sung directly on top of mainstream pop songs, or the artist’s elaborately collaged “muted” magazine advertisements (such as Muted Car Ad, Muted Detergent Box and Muted Coke Bottle, all on view in The Hateful Years), Flood’s work involves a very specific brand of cultural appropriation and critique. While such peer artists as Richard Prince and Sherri Levine were casting a cold, detached gaze on their “stolen” pop material, Flood’s use of purloined images always projected something hot and inflammatory, mutating things at once familiar and foreign. Capitol and commercial culture are frequent and crucial themes in these early works. In a series of text collages made in the early ‘80s while he was a file clerk for Texaco, the artist used company letterhead as the base for works such as Service Your Master, a piece which features a cut up and re-purposed Master Card ad which repeatedly incites the viewer to apply for a card and then submit to the bondage of debt. Though the text element of Service is a transparent critique of consumer culture, the act of constructing it out of office materials while working at Texaco has the more complicated affect of reconfiguring the power relationship between worker and corporate employer. These works subtly deactivate the American mythology that labor offers spiritual and moral redemption.

Flood’s porn collages are his most complicated interventions. As befitting what for many will qualify as obscene and demeaning (i.e., pornography), the artist savages and heightens the obscenity with incredibly vulgar and outrageous but humorous insertions. This body of work within Flood’s oeuvre removes porn from the realm of titillation and insists, by way of grotesque collage,

on just how interchangeable and commodified our body parts can be.

In the work on view in The Hateful Years, there are no pretensions to mastery. Flood availed himself of found materials, particularly in terms of painting. Many of the works on view at Luxembourg & Dayan were painted additions to, or an obscuring of, a pre-existing image. Flood has often used found paintings - sourced from flea markets, garage sales, and dumpster diving – to fashion anti-billboards for his America. And here the artist set his sights on antagonistically engaging the art world itself, critiquing its self-congratulatory, self-reflexive tendencies. (Culturcide’s first single, Another Miracle/Consider Museums as Concentration Camps, was released in 1980.) Irreverent, independent, and political with an aesthetic edge, the works on view in The Hateful Years evolved and accumulated outside the reach of the New York cognoscenti while foreshadowing many of the themes and visual strategies now common among a generation of high profile contemporary artists, including Nate Lowman, Joe Bradley and Josh Smith. Flood’s legacy is at work in the cur- rent production of these younger artists - practitioners who have “discovered” his work over the last years through group and solo exhibitions since about 2008.